Feasibility Studies Explained: Evaluating Project Viability

Published 31-MAR-2023 10:10 A.M.

|

16 minute read

Building a mine or a processing plant is not cheap.

After making a discovery and establishing the size and scale of the deposit, a company needs to work out whether it makes financial sense to put a mine into production.

Before spending a large amount of capital to develop a project, there needs to be a high degree of certainty that the investment will deliver the company (and YOU, the shareholder) a return on investment.

This is where feasibility studies comes in.

Discover the 5 Battery Materials Stocks we’ve Invested in for 2023

What is a feasibility study?

A feasibility study is a detailed document that evaluates a project to determine whether the defined deposit can be extracted economically.

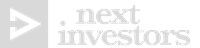

The feasibility study fits in the middle of a project’s life cycle which is as follows:

- Exploration - The company makes a discovery

- Definition - The company identifies how big the deposit is

- Feasibility studies - The company evaluates the viability of the project and whether it is worthwhile investing more capital to progress

- Development - The inputs from the feasibility study are used to develop the project

- Production - Start shipping and processing the commodity for sale to market (making money)

It’s important to note that feasibility studies are based on assumptions, so the more accurate the assumptions the better the feasibility studies will be.

Why do companies undertake feasibility studies?

Imagine a company has explored an area, made a discovery, and defined how big it is...

Why can’t they just dig it up and sell the product?

Companies have tried to do that in the past, but what tends to happen is that things cost much more than expected, development is delayed, commodity prices fluctuate, or operational issues make projects completely unprofitable.

The feasibility study is a critical step in the “planning” process which showcases whether or not an in-ground resource can be developed into a profitable mine.

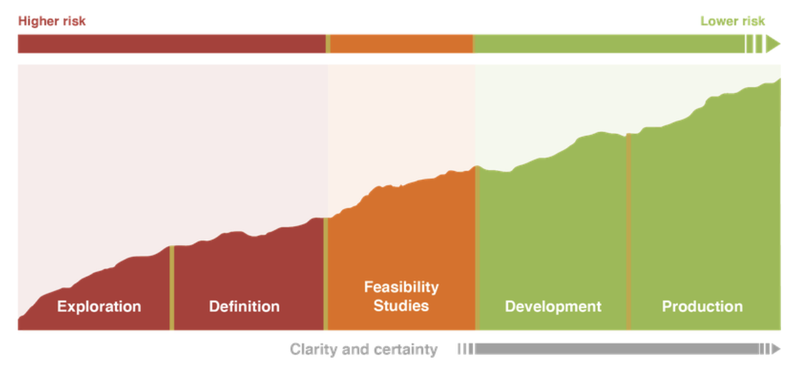

There are four key aspects that a feasibility study address:

- Technical feasibility: How will the deposit be mined, extracted, processed and shipped to market?

- Economic feasibility: What are the upfront costs of the project? What are the operating costs of the project? What price will the commodity be sold for? Will investors make a return from the project if it is put into production?

- Legal feasibility: Are all the permits and licences in place to begin construction on the project?

- Environmental / Social feasibility: What is the effect on the environment? How will waste products be disposed of? What natural resources are needed (i.e. water)? Has the project got the support of the local community?

If a project has begun without addressing each of these key pillars it will likely fail (or at least be extremely inefficient) and, more likely than not, investors will lose money on the project.

Failing to plan is planning to fail.

Imagine trying to develop a project only to realise that the necessary permits aren't in place.

Or imagine trying to develop a project only to realise that the company is losing more money than it is making due to production inefficiencies.

These things CAN and DO happen during the development and production phases of a project, which means that the companies will want to mitigate as much risk out of the project as possible.

Note, feasibility studies aren’t limited just to mining projects.

Infrastructure projects, company acquisitions, really any project with large capital expenditure will generally use feasibility studies to help make decisions.

It is the most important part of the planning phase and will help investors and financiers make decisions about funding the project.

What are the different types of feasibility studies?

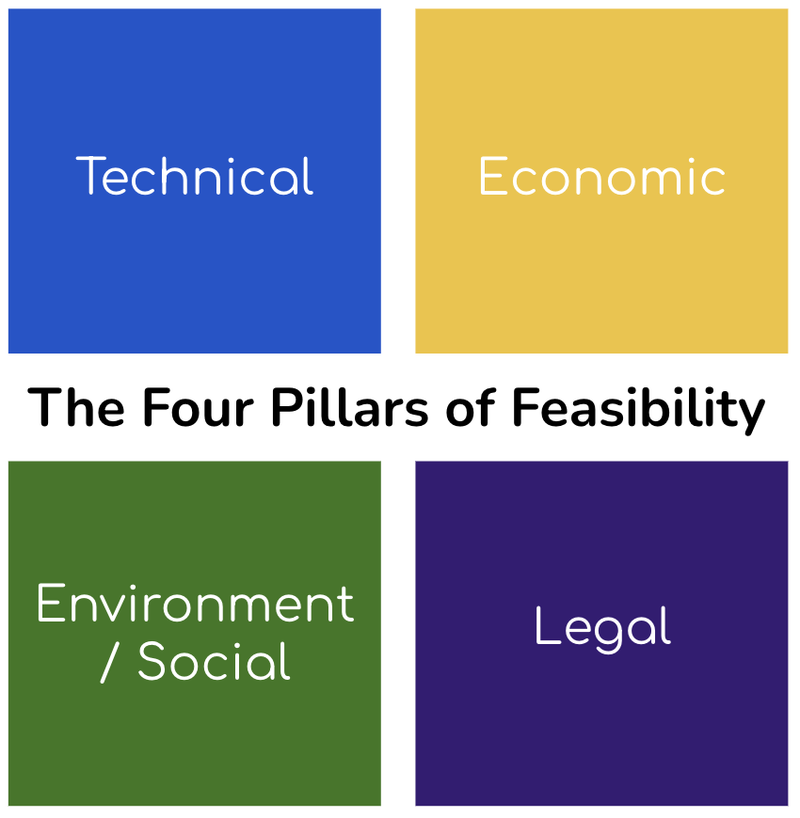

The four main types of feasibility studies are:

- Scoping Studies

- Pre-Feasibility Studies (PFS)

- Definitive Feasibility Studies (DFS)

- Bankable Feasibility Studies (BFS).

Each provides progressively more certainty around the four key aspects of project feasibility mentioned above.

These studies provide for a snapshot of a projects economics so as to support a decision by potential project financiers — often joint venture investors or banks — that the project is worth funding.

This decision is what’s called a Final Investment Decision (or FID) and is what comes after a feasibility study is well understood.

Note, the FID can come anytime after one of the studies is completed (often after a DFS), it all depends on the risk appetite of the project financier.

Below is a deep dive on all four of the feasibility studies:

Scoping Study / Preliminary Economic Assessment

Also known as a “conceptual study”, a Scoping Study (or the Preliminary Economic Assessment, PEA) provides a high-level snapshot of a project's economic potential.

Think of this as an initial appraisal early in the life of the project to determine whether a project warrants spending more capital on.

The Scoping Study is based on initial data collected from drilling, and metallurgical testwork done in the exploration and definition phase.

This data helps inform the company’s assumptions as to how the project will eventuate from a technical, economic, and environmental perspective.

At this stage there may be some estimated production numbers that investors can sink their teeth into, but these figures are relatively unreliable given they are only based on high level assumptions.

The data in a Scoping Study should outline the key project opportunities and risks, but it is not accurate enough to carry out a meaningful assessment of the project’s economic viability.

At this stage, investors should have enough information to make very rough estimates of costs and the potential return that could be delivered by developing the project.

We like to call these “back of the napkin” calculations.

Pre Feasibility Study

If the Scoping Study indicates that the project has potential to be economically viable, the company will likely move forward with a Pre-Feasibility Study.

At a very high level the name summarises the study well, it is what comes before the more detailed feasibility study - hence why it is called a “Pre” feasibility study.

A PFS will typically include initial capital and operating cost estimates (CAPEX, OPEX) and are accurate enough to compare various project configurations.

As exploration and engineering design move forwards, the Pre-Feasibility Study phase may develop into a series of iterative assessments that are gradually updated and modified.

By this stage, the company will have a fairly detailed idea of how the project stacks up financially.

Definitive Feasibility Study

This is the next feasibility study that a company will undertake before shopping its project around to potential financiers and investors.

Building a mine could cost hundreds of millions of dollars, so the company will want to make sure that it has removed as much doubt as possible around project economics and viability.

The overall goal is to demonstrate to investors, financiers, and other stakeholders whether the project can be constructed and operated profitably while meeting all relevant regulatory and environmental requirements.

The results of the study are presented in a detailed report that includes information such as the project’s scope/schedule, operating and capital expenses (OPEX and CAPEX), revenue projections, cash flow analysis, and sensitivity analysis.

It is useful for investors, lenders, and other stakeholders to evaluate the project’s potential and make informed decisions ahead of proceeding with the project development.

Overall, a DFS provides a thorough and detailed overview of a proposed project, and is an essential step in the project development process.

At this stage, the company tends to be in a position where a project does not require any further work to be put into development, but simply needs financing.

Bankable Feasibility Study

Sometimes companies will choose to take the DFS to the next level by completing a Bankable Feasibility Study (BFS).

The BFS is done with the highest level of certainty and does what it says it does - makes the feasibility study detailed enough that it can be shopped around to banks for debt funding.

It will often come after a company has secured pricing for its product with offtake (take or pay) agreements, licences to construct the project, and everything in place bar financing.

This study has more to do with project financing than geology and includes information about lending and investment conditions, payback periods, and internal rate of returns.

At this stage, the feasibility study process is largely complete, it now becomes a case of whether or not the project gets funded or not.

How to read a table of project economics from a feasibility study

Most feasibility studies will provide a snapshot of a project’s economics.

These often come in the form of a table, and display the key outputs of a feasibility study.

A lot of assumptions go into determining these key figures, which can be found in the details of the study, but the top line items are the ‘money shot’ for investors and financiers.

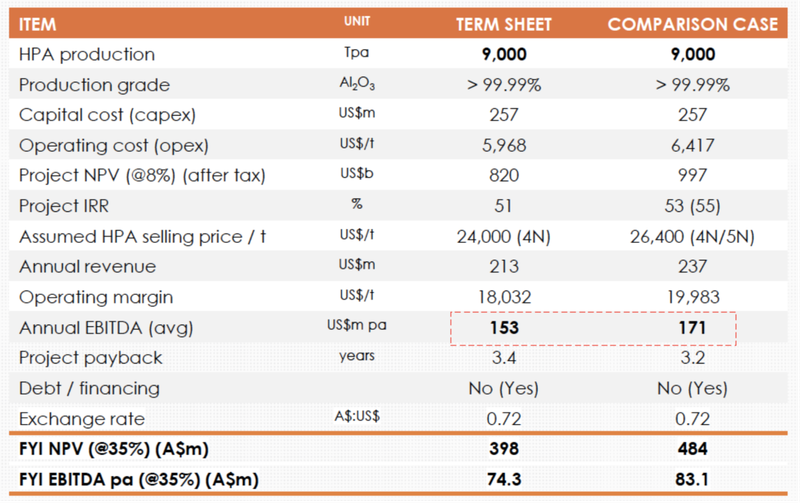

Here is an example of the Definitive Feasibility Study summary for FYI Resources (ASX:FYI):

There are some key terms that you will need to know in this table:

Production

The production for mining projects is often reported in “tpa” (or tonnes per annum) and it represents the amount of ore produced from the mine each year.

Multiplying this number by the expected price of the commodity will generally give you an idea of the potential revenue of the product.

For some commodities, like lithium or graphite, there may be multiple end products from the same mining deposit.

In these scenarios, the production numbers will be separated out to show the different end products with different prices attached.

Capital Cost (CAPEX)

This number represents the upfront capital cost to construct the project and is affected by things like labour costs, the price of steel and other raw materials.

Operating Cost (OPEX)

This number represents the ongoing project operating costs, or the expenses involved in reaching the level of production outlined in the feasibility studies — think energy prices, transportation costs, labour costs, and taxes.

Project NPV

The project Net Present Value (NPV) is the $ value today of the potential return to a company if a project is developed based on all of the assumptions made in a feasibility study.

Basically, if an NPV is $100M, it is saying the project is worth $100M in potential returns if developed (assuming all of the assumptions in the feasibility study play out).

At the feasibility stage, the project NPV will often be much higher than the company’s market capitalisation — this is often because there is uncertainty around whether or not a project will be developed or around the assumptions/risks in the feasibility study.

However when comparing a project NPV to the company’s market cap it is important to note what percentage ownership the company has over the project and whether it has any other assets/projects.

At the time FYI Resources’ DFS was published (above), FYI owned 35% of the project, which suggests that all going to plan, and all else aside, the company’s value grow to be 35% of the total NPV of the project.

Project IRR

The project IRR or Internal Rate of Return, represents the potential return to investors who are willing to fund the project.

The higher the IRR, the more attractive the project is from a financial perspective, again all else considered.

Consider that with the current risk-free interest rate being around 5%, a project IRR should be higher than this to reflect the risk involved and reward investors.

Project Payback Period

Given the large upfront cost of building a project, the payback period represents the amount of time for investors to “breakeven” by making back their capital invested.

Given most project lifecycles are 5-10 years+, investors typically want to be paid back their initial investment as soon as possible.

The shorter the project payback period, the more attractive the investment.

What happens when projects don’t stack up?

Sometimes companies will undertake a feasibility study and then fail to raise the money needed to develop a project.

This can happen for a number of reasons, perhaps the base commodity is out of favour, economic conditions are poor, or the project economics don’t stack up to investors’ risk profiles at the time.

In this scenario, the company has a few options.

- Undertake more exploration and definition to increase the size of the deposit

- Improve the technical aspects of the project or metallurgy results to improve the economics of the project

- Sit on the project and wait for the commodity or market to return to favour

If the company does one or more of these things it will likely need to “update” their Feasibility Study with all of its new learnings or higher commodity prices.

Another factor can also be the time since the feasibility study was completed.

Typically feasibility studies that are more than two years old will likely be out of date for potential project financiers, and the company will need to update the study to reflect the new price of commodities and inputs.

Remember, a feasibility study is only as good as the assumptions it is based on.

Assumptions that are made two years ago will often be outdated. This is why updated feasibility studies are important for companies looking to move their projects into development.

How to read the details of a feasibility study

Feasibility studies can be long, sometimes more than 100 pages - so it is important to know what to look for.

The best way to start is to look at the headline numbers in the Table of Project Economics and then dive deeper into the details of how those project economics were created.

All feasibility studies are based on assumptions, so it is important that you as an investor evaluate the assumptions that the company has made and make an independent assessment as to whether you think those assumptions are reasonable.

Here are the main sections of the feasibility studies that investors generally look at:

Commodity Pricing

For most commodities pricing is transparent (gold, oil, etc).

However, some more specialised commodities (lithium, graphite, hydrogen) require a more detailed analysis of the commodity price.

Pricing will generally be based on certain assumptions about the demand for that commodity at some point in the future, and it will be up to you whether you think that the forecast demand aligns with your expectations.

If a company has signed an offtake agreement (a prepayment for part or all of its production), then the commodity pricing can be easier to identify.

Cost Pricing

Costs can and do change, especially in an inflationary environment.

Investors need to be aware of this when evaluating the input costs that the company has used such as energy, fuel, and labour.

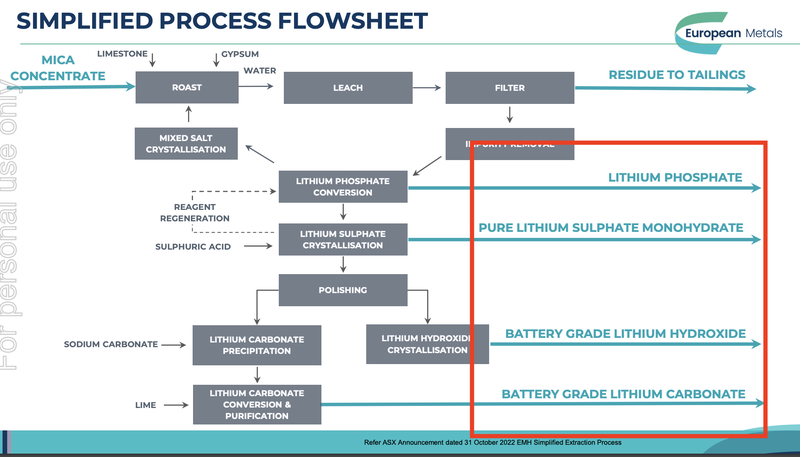

Flow Sheet

A flow sheet talks to the technical feasibility of the project.

It is a detailed design of how the processing plant will take the ore from the ground and turn it into a saleable product to market.

Here is an example of a processing flowsheet from our lithium Investment European Metals Holdings (ASX:EMH):

Front End Engineering Design (FEED)

The Front End Engineering and Design (or FEED) is the process by which a consulting team will evaluate the project from a technical perspective and make improvements to things like the flow sheet, mining process, and waste disposal.

It will help design the processing infrastructure and the specifics of how the ore will be mined and processed for sale in the market.

Environmental Impact Assessment

The Environmental Impact Assessment is an important part of the process that will determine whether the impact of the project falls within the guidelines of the country from an environmental perspective.

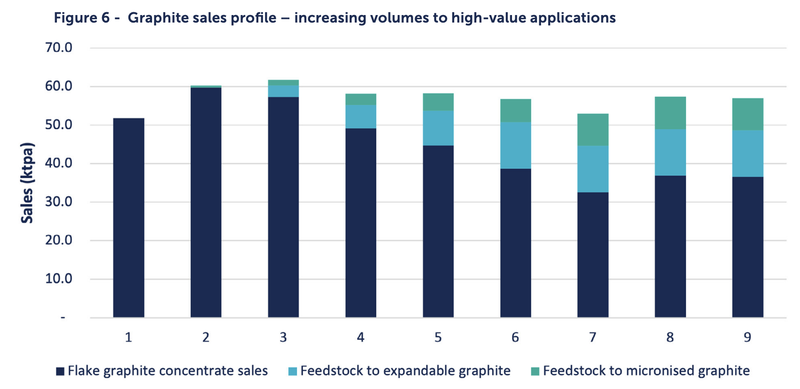

Production Schedule

The production schedule represents the amount of tonnes of product that the company will sell each year.

Depending on how the project is designed this may be larger in the earlier stages of the project or in the later stages, depending on the type of deposit.

Here is an example of a production schedule from our 2021 Wise-Owl Pick of the Year Evolution Energy Minerals (ASX:EV1):

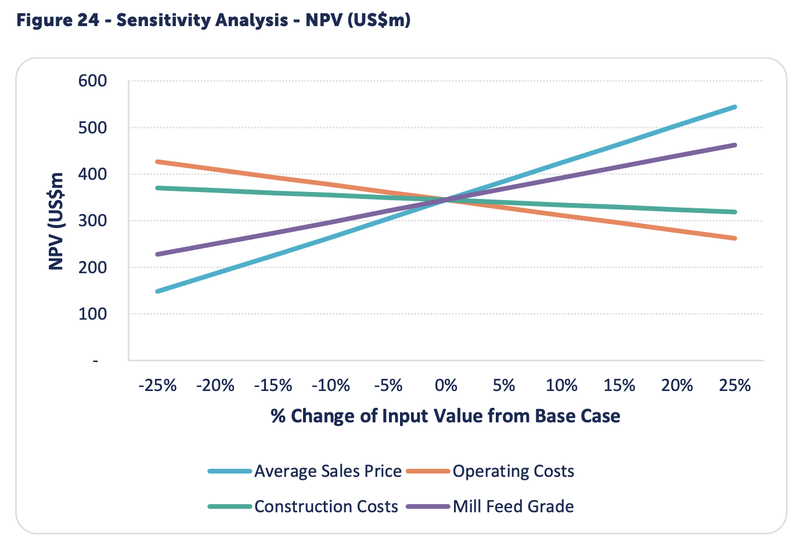

Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis is an important part of the feasibility study, as it shows how changes in assumptions can change the overall economics of the project.

Remember, feasibility studies are based on assumptions, so if those assumptions change then the project economics change too.

Here is a sensitivity analysis from EV1, as you can see, if the commodity price increases then so does the project NPV:

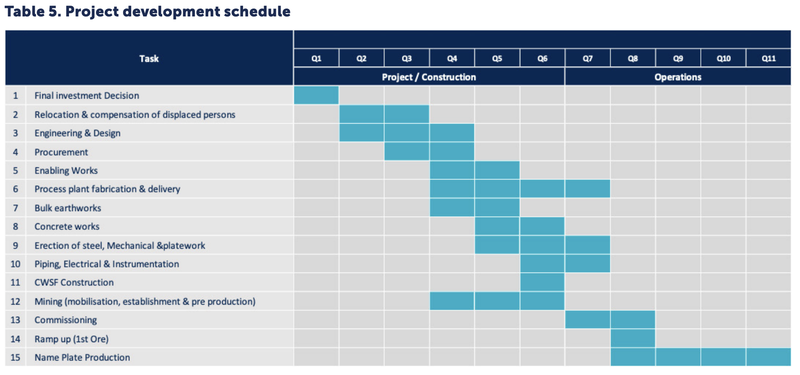

Project Schedule

This is an aspirational timeline from first shovel to production.

These timelines often sit within a gantt chart and detail all the milestones (in order) that the company will need to tick off in the “development” phase to reach production.

Conclusion: Why feasibility studies are so important

The purpose of feasibility studies is to convince potential financiers to fund a project.

Funding will only come when there is a degree of certainty that the project is viable from a technical, environmental, legal and, most importantly, economic perspective.

Usually hundreds of millions of dollars are required to bring these projects online, so it is understandable that financiers want to remove as much doubt about the project's feasibility as possible BEFORE writing the big cheque.

Getting a project funded is hard, so those few companies that succeed in reaching a Final Investment Decision are generally rewarded with a big share price increase.

Remember, feasibility studies are based on assumptions and it is up to you as the independent investor to evaluate whether the assumptions that the company makes are reasonable.

Circumstances can and do change for better or worse, so it is important to realise that what was not economical today, may be economical in a different environment in the future.

Always pay attention to the underlying commodity of the project and follow the story closely to see if circumstances change.

General Information Only

S3 Consortium Pty Ltd (S3, ‘we’, ‘us’, ‘our’) (CAR No. 433913) is a corporate authorised representative of LeMessurier Securities Pty Ltd (AFSL No. 296877). The information contained in this article is general information and is for informational purposes only. Any advice is general advice only. Any advice contained in this article does not constitute personal advice and S3 has not taken into consideration your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Please seek your own independent professional advice before making any financial investment decision. Those persons acting upon information contained in this article do so entirely at their own risk.

Conflicts of Interest Notice

S3 and its associated entities may hold investments in companies featured in its articles, including through being paid in the securities of the companies we provide commentary on. We disclose the securities held in relation to a particular company that we provide commentary on. Refer to our Disclosure Policy for information on our self-imposed trading blackouts, hold conditions and de-risking (sell conditions) which seek to mitigate against any potential conflicts of interest.

Publication Notice and Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is current as at the publication date. At the time of publishing, the information contained in this article is based on sources which are available in the public domain that we consider to be reliable, and our own analysis of those sources. The views of the author may not reflect the views of the AFSL holder. Any decision by you to purchase securities in the companies featured in this article should be done so after you have sought your own independent professional advice regarding this information and made your own inquiries as to the validity of any information in this article.

Any forward-looking statements contained in this article are not guarantees or predictions of future performance, and involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, many of which are beyond our control, and which may cause actual results or performance of companies featured to differ materially from those expressed in the statements contained in this article. S3 cannot and does not give any assurance that the results or performance expressed or implied by any forward-looking statements contained in this article will actually occur and readers are cautioned not to put undue reliance on forward-looking statements.

This article may include references to our past investing performance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of our future investing performance.