What is an ASX-listed shell?

Published 01-JUN-2022 15:02 P.M.

|

12 minute read

Regular readers would be well aware that almost all of our investing happens at the smaller end of the market, where the market caps typically are less than $100m.

In this end of the market we are looking to allocate capital in companies with strong management teams and projects that we think can grow in value over time.

Our theory is that as the project develops and key milestones are achieved, the market will take an interest in the stock and the market cap (and share price) will re-rate to reflect the new value added to the project.

This isnt always the case though, no matter how good the people behind a project are, sometimes these projects dont get off the ground and can become “stranded”.

These situations often come about after a company has tried to execute on an objective (drilling for gold, building a new product, developing a drug), but a key risk has materialised and rendered the project stranded.

Investors who have been involved in the micro cap market as long as us will know that these companies are commonly referred to as “shells” and are usually fairly easy to spot.

These shells then become empty vehicles that are used to bring in new projects/ventures and basically give the listed company a new lease of life.

How does a listed company become a shell and how to spot them

Most of the ASX listed shells we come across are junior exploration companies that have completed a drilling program and did not find enough to continue funding further exploration.

However, shells can appear in other industries like tech (building some sort of website or app) or retail (like pivoting to hand sanitisers in March 2020) that fail to achieve any level of traction before funding runs out.

Once the company can’t fund its projects any more, it may walk away from the asset or technology and transition into the “shell” stage of a company’s lifecycle.

Staying with the example of a junior exploration company, signs that a company is in the “shell” stage are as follows:

- The company goes into maintenance mode - The listed company will transition from doing expensive drilling programs to keeping its tenements in good standing by meeting minimum expenditure requirements. Sometimes they will run small scale exploration programs that are cheap to operate in the hopes of finding interesting targets, but will rarely commit any serious amount of cash to these programs.

- Cash-burn reduces significantly - The company will have little/no exploration expenditure with the quarterly cash flow statements showing that most of the spend throughout the quarter was on corporate and administration.

- Board and management teams will be restructured - With most of the previous executive teams becoming legacy hires related to the assets that the company is moving away from. Shells will often see changes both at the board level and at the management level, with fresh faces brought in to help develop new projects/ventures.

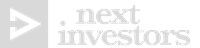

This point where a listed company gives up on a certain asset/project and decides to move on to something new is almost always correlated with the time most shareholders are understandably selling for the sake of getting out - the capitulation stage in the image below:

Therein lies the opportunity for the investors willing to do the research and take on the risks that come with investing in shells.

Investors are given an opportunity to buy shares off stale shareholders who are looking to exit a particular stock, because their investment thesis did not pan out.

We look at shell-investing as a way of getting in at the ground level, akin to investing in venture capital style seed raises. It is almost like investing in what has become famous in the US as “Special Purpose Acquisition Vehicles (SPAC’s)”.

Of course, just like seed investing, this comes with massive room for growth at extremely high risks (which we will touch on later in this article).

Why do shells exist?

Shells act as a gateway for deal-makers to get projects onto the ASX without having to go through a lengthy IPO process (Initial Public Offering).

IPO’s require a lot of administration work and can take a long time to get done.

There are obvious benefits to doing an IPO, companies are able to raise funds at much higher valuations.

The biggest disadvantage is that it takes a long-time to complete and they are not cheap. This is where shells come into play.

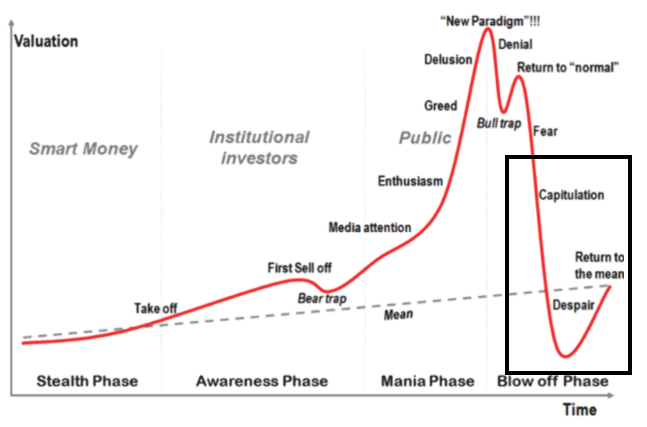

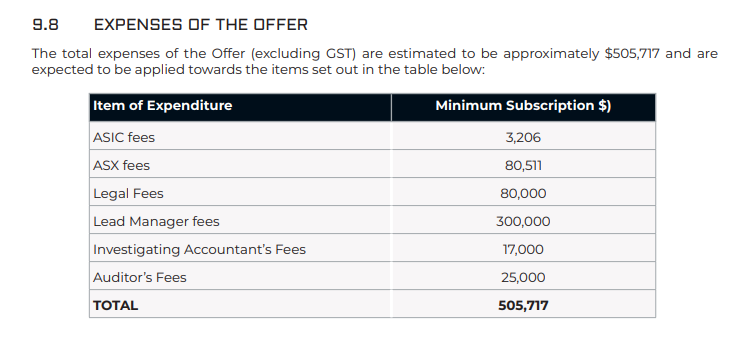

Below are images of two IPOs with the expenses paid to list on the ASX ranging from $505k to $4.6M. Of course these fees can be a lot higher depending on the valuation of the listing.

In the example below BeforePay had to pay ~$4.6M to list after raising $35M.

Basically, they spent 14% of the cash raised just to get listed.

Conversely, shells are already actively trading on the ASX and don't need to go through the expensive and lengthy IPO process.

Assets can be brought in via a process called a reverse take-over (RTO).

Generally, these types of transactions happen by way of an acquisition by the listed company. Below is an example of how a junior exploration company would get an RTO done:

A junior exploration company acquires new projects.

The junior explorer identify’s new projects where the shell’s new management team and board of directors see value.

The vendors of the project then come to an agreement to sell these projects to the listed shell by way of a sale deed.

These sales deeds often have a mix of shares and cash as consideration and can sometimes require shareholder approvals before a deal is completed.

Once approved and the deal finalised, the new projects are now owned by a listed company and can raise capital off the back of this to aggressively start exploring these projects.

The only costs involved in these deals are the legal costs of putting together a sale deed and the due diligence on the projects being acquired. Nowhere near the amount spent on an IPO and at a fraction of the time.

In the US markets, SPACs have become really popular because they offer very similar pathways to a listing for much larger companies.

The best way to understand what a shell is and what it offers is to view it as the ASX’s version of a SPAC with the only difference being that they weren't set up specifically to acquire new projects but instead become shells over time.

What makes a good shell play?

We think shell investing is almost formulaic, it requires a rigorous research process, patience and just like with all investing, a little bit of luck.

We have been investing in small caps for 20+ years and in our investment lifetime we have seen some shells turn into not only ASX top 50 companies but some of the biggest in the world in their sectors.

One that comes to mind is Northern Star Resources (ASX: NST).

Up until the end of 2009, NST had an $8m Market Cap and was considered a shell with some uranium exploration prospects that had minimal work happening to them. NST was effectively in “maintenance mode”, where it spent the minimum amount on exploration activities to remain listed.

At the time the primary operation for NST was “reviewing project opportunities” and for a long time NST was operated as an ASX listed shell.

That all changed in 2010 when NST acquired the Paulsens gold mine for $15m in cash + a royalty of $200/Oz up to a maximum of $12m.

Overnight NST went from a shell with no assets of interest to owning an asset where the board of directors and management saw value that others hadnt.

Northern Star ran with that acquisition and went on to become what it is today, an $10 billion behemoth that is now in the top-10 largest gold producers in the world (by market cap).

So what makes an interesting shell investment?

Below is a list of the things we look for when assessing shell investments:

1. The board and the management team:

We are looking for proven deal-makers at the board level.

Ideally, these are people who have successfully built companies from the ground up in the past.

These people are generally unlikely to waste their time with a $5m market cap ASX-listed shell so their involvement is generally an indication that they may be setting up to bring in projects where they see value and may think the markets are underappreciating.

We invest, hoping to see these guys bring in these projects, raise fresh capital and unlock the value in the asset that the rest of the market may have missed.

Ideally, these guys will have some shares in the shell but this isn't a must, as they may get involved in future capital raises.

We are also looking for proven, experienced management teams.

Generally, the board members who are preparing to bring in new assets to these shells will also bring in operators who will run the company on a daily basis looking to unlock whatever value is in the company’s new projects.

2. Shareholders and major backers

We are looking to see patient capital backing the shell.

Generally, the same deal makers who are on the board of these shells are also major shareholders. We are always looking to see who the major shareholders are, whilst the company is being operated as a shell.

When looking at the top 20 shareholders we like to see that there is experienced, long term focused patient capital invested alongside us.

Just like in team sports to be successful you need to have a good team around you. Shells are no different.

The deal-makers at the board level will generally move from venture to venture with the same group of investors around them. We look for similar registries from the other successful deals these people have done.

Sometimes the shareholder register needs to be restructured and this is where things like a capital consolidation comes into play. Where we think this is a possibility we look to wait and see the new board/management get all of this work done before looking to build our position.

3. Capital structure

Last but not least we look at the shell's capital structure.

This generally gives us an indication of how close a shell is to being stuffed with new assets. For us, there are specific things that are important.

First, is the shares on issue: We like to see a small number of shares on the issue before a new deal is done BUT generally, this won't be the case with shells.

As we discussed earlier in this article, shells come about after attempts to make a company out of other assets, this generally means a lot of cash has been raised and burnt on previous ventures.

This naturally means there are a lot of shares on the issue, in these circumstances a capital consolidation is likely to occur so we will wait for this to happen before making an investment.

Second, is a low market cap or enterprise value: Naturally, as shells don't have any assets that are of interest to the market we don't like to pay up for no particular reason.

Ideally, we like to see a market cap <$5M, BUT this can depend on the calibre of the deal makers involved, the market sentiment at the time and the amount of cash in the bank.

If the cheapest shell on the ASX at the time is trading with a market cap of $8M, then we would value other shells relative to this.

If the shell has a large cash balance and meets all of our other investment criteria then we look at the enterprise value of a company, for example a shell may have a $15M market cap but have $10M in cash, this may still be an attractive opportunity for us.

Third, we like shells with no debt: This doesn't need any explaining, we view shells as new ventures and naturally don't want to be holding any debt on inception.

Risks to know before investing in shells

We like to compare investing in shells to participating in seed capital raises.

As a result there are specific risks that need to be considered when investing in shells, that make it a lot riskier than investing in already established ASX listed companies.

Below are a list of risks that need to be considered:

Activity risk:

There is a risk that the directors are unable to find a suitable project for the shell.

If this happens the company has no core assets to fall back on and if the company is unable to maintain its activity levels there is a risk the company does not meet the ASX’s minimum activity requirements.

This can lead to the company being suspended or in the worst case scenario could even be delisted.

Market is not interested in the acquired project:

Venture capital investors who participate in seed raises are putting their faith in the management/directors of a company to put the company’s cash to use in the best possible way.

Investing in shells is no different.

There is always a risk that the directors complete a deal that the market is not interested in or the directors over pay for a new project which the market then reacts to in a negative way.

Capital structure changes:

Almost always the deals put together involve payments in shares and cash.

Sometimes the deals can see large amounts of shares issued to the vendors of the projects being acquired. This means a company’s shares on issue can go from relatively low to a much larger number.

This will mean large amounts of dilution for existing shareholders and will put some short term pressure on the company’s share price.

These are inherent risks when considering shell investments, we try to mitigate the probability of these risks occurring by doing our research and ensuring the deal-makers have been there and done it all before.

Our investment strategy with shells

We think that investing in shells should be extremely procedural.

Almost all of these companies have assets that the market is no longer interested in or that have not managed to reach any level of commercial success.

In this scenario, we like to remain objective and make decisions based on a set investment process.

Our investment strategy with shells is as follows:

- Identify the shell - You can screen for shells by looking for ASX listed companies with <$15M market cap, and from there establish if the company has developed or stranded assets.

- Conduct thorough due diligence - We will then go through our rigorous due diligence process mostly focussed on doing a deep-dive into the board/management team, shareholders/major backers and the capital structure of the shell.

- Workout what level the dealmakers are set - We will then try to work out the volume weighted average price (VWAP) for the dealmakers of the deal is, where these people have purchased their shareholdings will be an indicator of where they see value in the shell. The closer we can enter to the price these people have purchased at the better.

- Start building position - Assuming the shell ticks all of our boxes we will then begin slowly buying our position on-market and look to top-up in any entitlement offers, rights issues or other capital raises.

- Hold through to a deal being done and then re-asses - At this stage, we are fully invested and patiently wait for a deal to be done. After the shell gets a new lease of life we will reassess our position depending on whether or not we think the dealmakers have brought in an interesting enough project.

At this stage it is all about the calibre of the Board, Management team and the quality of the assets acquired.

Having done most of our research before a deal is done we are generally invested for the long-term but if we see any red flags we are quick to move on from these companies.

General Information Only

This material has been prepared by StocksDigital. StocksDigital is an authorised representative (CAR 000433913) of 62 Consulting Pty Limited (ABN 88 664 809 303) (AFSL 548573).

This material is general advice only and is not an offer for the purchase or sale of any financial product or service. The material is not intended to provide you with personal financial or tax advice and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Although we believe that the material is correct, no warranty of accuracy, reliability or completeness is given, except for liability under statute which cannot be excluded. Please note that past performance may not be indicative of future performance and that no guarantee of performance, the return of capital or a particular rate of return is given by 62C, StocksDigital, any of their related body corporates or any other person. To the maximum extent possible, 62C, StocksDigital, their related body corporates or any other person do not accept any liability for any statement in this material.

Conflicts of Interest Notice

S3 and its associated entities may hold investments in companies featured in its articles, including through being paid in the securities of the companies we provide commentary on. We disclose the securities held in relation to a particular company that we provide commentary on. Refer to our Disclosure Policy for information on our self-imposed trading blackouts, hold conditions and de-risking (sell conditions) which seek to mitigate against any potential conflicts of interest.

Publication Notice and Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is current as at the publication date. At the time of publishing, the information contained in this article is based on sources which are available in the public domain that we consider to be reliable, and our own analysis of those sources. The views of the author may not reflect the views of the AFSL holder. Any decision by you to purchase securities in the companies featured in this article should be done so after you have sought your own independent professional advice regarding this information and made your own inquiries as to the validity of any information in this article.

Any forward-looking statements contained in this article are not guarantees or predictions of future performance, and involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, many of which are beyond our control, and which may cause actual results or performance of companies featured to differ materially from those expressed in the statements contained in this article. S3 cannot and does not give any assurance that the results or performance expressed or implied by any forward-looking statements contained in this article will actually occur and readers are cautioned not to put undue reliance on forward-looking statements.

This article may include references to our past investing performance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of our future investing performance.